A new study from South Africa comparing three different front-of-package (FOP) labeling schemes found that a nutrient warning label helped more participants correctly identify unhealthy products and more strongly reduced their intention to purchase those products, compared to a “multiple traffic light” label and a Guideline Daily Amounts label.

These findings, published in Appetite, come at an important time as South African policymakers consider draft regulation for the country’s first mandatory front-of-package label. While research from other countries has found that nutrient warning labels are the stronger FOP label option for identifying and discouraging consumption of unhealthy foods, some studies find that other labels, such as the traffic light, can also be effective. This suggests that context plays an important role and underscores the importance of testing a label designed specifically for South Africa.

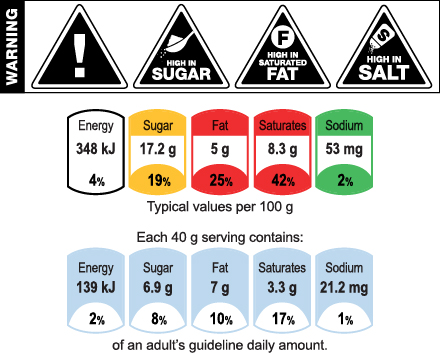

“It was important to create a warning label for South Africa that can help people from different language backgrounds and literacy levels make informed decisions on what to buy and eat,” said Makoma Bopape (left), first author and Senior Lecturer in Human Nutrition and Dietetics at the University of Limpopo. “We achieved this using a triangle shape and exclamation mark that are associated with ‘warning’ in South Africa and by including icons for each nutrient, for example a saltshaker for sodium.”

“It was important to create a warning label for South Africa that can help people from different language backgrounds and literacy levels make informed decisions on what to buy and eat,” said Makoma Bopape (left), first author and Senior Lecturer in Human Nutrition and Dietetics at the University of Limpopo. “We achieved this using a triangle shape and exclamation mark that are associated with ‘warning’ in South Africa and by including icons for each nutrient, for example a saltshaker for sodium.”

In a randomized controlled trial, researchers from the University Limpopo, the University of the Western Cape, the University of Antwerp, and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill compared how well the different label types helped South African consumers:

- Identify products high in sugar, salt, or saturated fat;

- Identify unhealthy products; and

- Reduce intention to purchase unhealthy products.

Participants were randomly selected from the general South African population, which resulted in a representative sample of nearly 2,000 households. They first answered questions about a set of fictional products with no FOP labels, as a control condition. Next, they were randomly assigned to one of the three FOP label conditions and shown another set of products featuring that label. They then answered the same questions about the labeled products.

Researchers measured how many participants in each group correctly identified products high in nutrients of concern (sugar, salt, and saturated fat), how many correctly identified products as unhealthy, and whether participants’ intention to purchase the unhealthy products changed after seeing them with a specific FOP label.

Key findings include:

- Participants who viewed the triangular nutrient warning labels were more likely to correctly identify unhealthy products compared to those who viewed the traffic light and Guideline Daily Amounts labels.

- The probability of correctly identifying products high in sugar, salt, or saturated fats was nearly twice as high for certain products when they featured a nutrient warning label vs. a traffic light or Guideline Daily Amounts label.

- Participants who viewed unhealthy products with nutrient warning labels reported a stronger decrease in intention to purchase them than those who viewed the traffic light or Guideline Daily Amounts labels.

“These findings are consistent with a rapidly growing body of evidence from around the world showing that warning labels are the most effective label type for helping consumers rapidly identify unhealthy foods — and perhaps more importantly, discouraging consumers from buying them,” said Lindsey Smith Taillie (right), co-author and Associate Professor of Nutrition at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

“These findings are consistent with a rapidly growing body of evidence from around the world showing that warning labels are the most effective label type for helping consumers rapidly identify unhealthy foods — and perhaps more importantly, discouraging consumers from buying them,” said Lindsey Smith Taillie (right), co-author and Associate Professor of Nutrition at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

This research comes on the heels of another study by Bopape, Taillie, and Rina Swart, senior author and professor in Dietetics and Nutrition at the University of the Western Cape, in which they examined how the same warning labels impacted parents’ food purchasing decisions and perceptions of unhealthy foods. When shown images of products with warning labels, parents said they would buy less of the foods with warning labels and switch to non-labeled, healthier options. Parents in the study also expressed that their children’s health was their top priority. Warning labels made them think about future health impacts if their children continued eating ultra-processed foods high in sodium, sugar, and saturated fat.

Like many countries worldwide, South Africa faces high rates of obesity and other diet-related diseases including type 2 diabetes, hypertension, and heart disease — all exacerbated by consuming a diet high in sugar, sodium, or saturated fat. In addition to helping consumers easily and more accurately identify foods high in nutrients of concern and discourage purchases of those products, requiring FOP warning labels on the least-healthy foods and drinks could incentivize industry to offer healthier product choices.

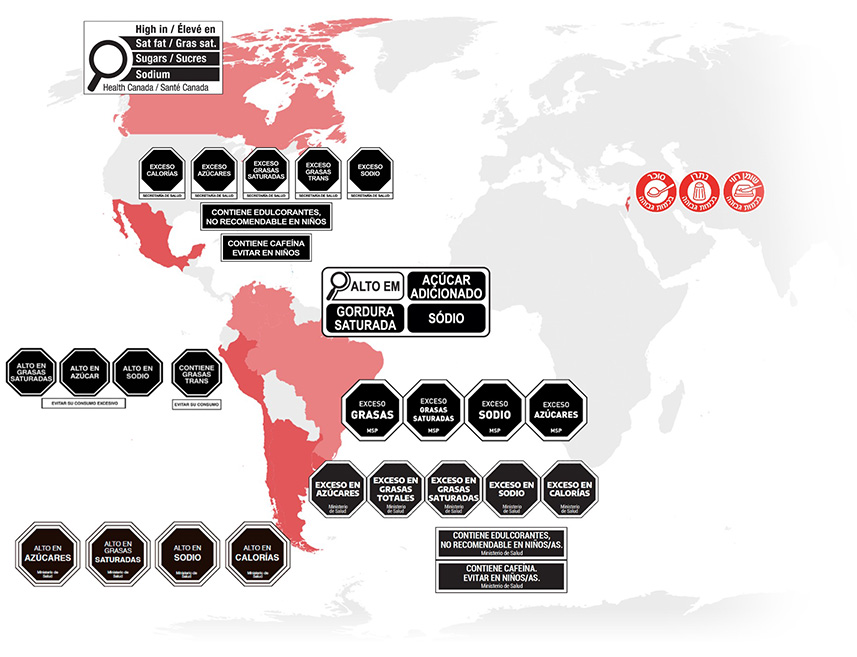

Policies using similar FOP nutrient warning labels have already been implemented or passed in ten other countries — most in the last three years. Evidence of their impact in Chile, where FOP warning labels have been required on unhealthy packaged foods and drinks since 2016, suggests that findings from experiments like this one in South Africa can translate into real, population-level changes in shopping behavior once a policy is implemented. In its first year, Chile’s FOP warning label policy was associated with a 24% drop in sugary drink purchases and declines in sodium (–37%), total calories (–24%), calories from sugar (–27%), and calories from saturated fat (–16%) purchased from all foods and beverages.

Policies using similar FOP nutrient warning labels have already been implemented or passed in ten other countries — most in the last three years. Evidence of their impact in Chile, where FOP warning labels have been required on unhealthy packaged foods and drinks since 2016, suggests that findings from experiments like this one in South Africa can translate into real, population-level changes in shopping behavior once a policy is implemented. In its first year, Chile’s FOP warning label policy was associated with a 24% drop in sugary drink purchases and declines in sodium (–37%), total calories (–24%), calories from sugar (–27%), and calories from saturated fat (–16%) purchased from all foods and beverages.

“If South Africa adopts the labels used in this study into the current draft regulations, ours will be the first African country and second country in the world after Israel to use a mandatory warning label with icons for different nutrients,” said Swart (left). “In addition to helping guide South African consumers toward healthier choices on what to buy, eat, and feed their families, this could provide important evidence for other countries that have diverse languages and literacy levels.”

This research was funded by Bloomberg Philanthropies.

For inquiries, contact Emily Busey.

Read the full paper in Appetite:

AUTHORS

Makoma Bopape

University of Limpopo,

University of the Wester Cape

Jeroen De Man

University of Antwerp

Lindsey Smith Taillie

UNC-Chapel Hill

Shu Wen Ng

UNC-Chapel Hill

Nandita Murukutla

Vital Strategies, New York

Rina Swart

University of the Western Cape

RESOURCES

Read more about the evidence for front-of-package labels.

View different front-of-package labeling policies around the world.