A new global review of school food policies published in Advances in Nutrition found that only 16% of countries worldwide have national policies restricting food marketing in schools, and only 25% have national policies restricting in-school sales of foods high in nutrients or ingredients of concern outside school meal programs. A mere 12% of countries have national policies restricting both.

Children around the world spend much of their days in schools, and many eat at least one meal a day there. This makes the school food environment a critical influence not only on what kids eat, but also potentially on their lifelong food preferences and dietary habits. To protect and enhance this environment, the World Health Organization and other public health leaders encourage policies to restrict children’s access and exposure to unhealthy foods and beverages in and around schools.

This scoping review study sought to assess the global landscape of national-level, mandatory policies related to food marketing and competitive food sales in in schools. To that end, researchers systematically searched all 193 United Nations countries for the presence of these national regulations:

- Restricting sales of competitive foods: “Competitive foods” are any foods or beverages sold in schools outside of a national school meal program. This includes foods sold in canteens, kiosks, tuck shops, vending machines, and from vendors coming onto school grounds.

- Restricting food marketing: Any oral, written, or graphic statements made to promote the sale of a food or beverage product. In schools, this can include featuring brand logos, spokes-characters, or product images on signs, scoreboards, vending machines, or other school equipment; branded sponsorship of incentive programs or school discount nights (e.g., at fast food restaurants), ads in school newspapers or yearbooks; fundraiser incentives; scholarships; and more.

“Decades of research clearly show that exposure to marketing for unhealthy foods and drinks harms children and adolescents and increases their risk for childhood obesity,” said first author Michelle Perry, MS, former Global Food Research Program research specialist and current doctoral student at Brown University School of Public Health. “This should be limited everywhere, but marketing especially has no place in schools. We expect the learning environment to foster knowledge and health, not entice food brand loyalty and eating behavior at odds with dietary guidelines.”

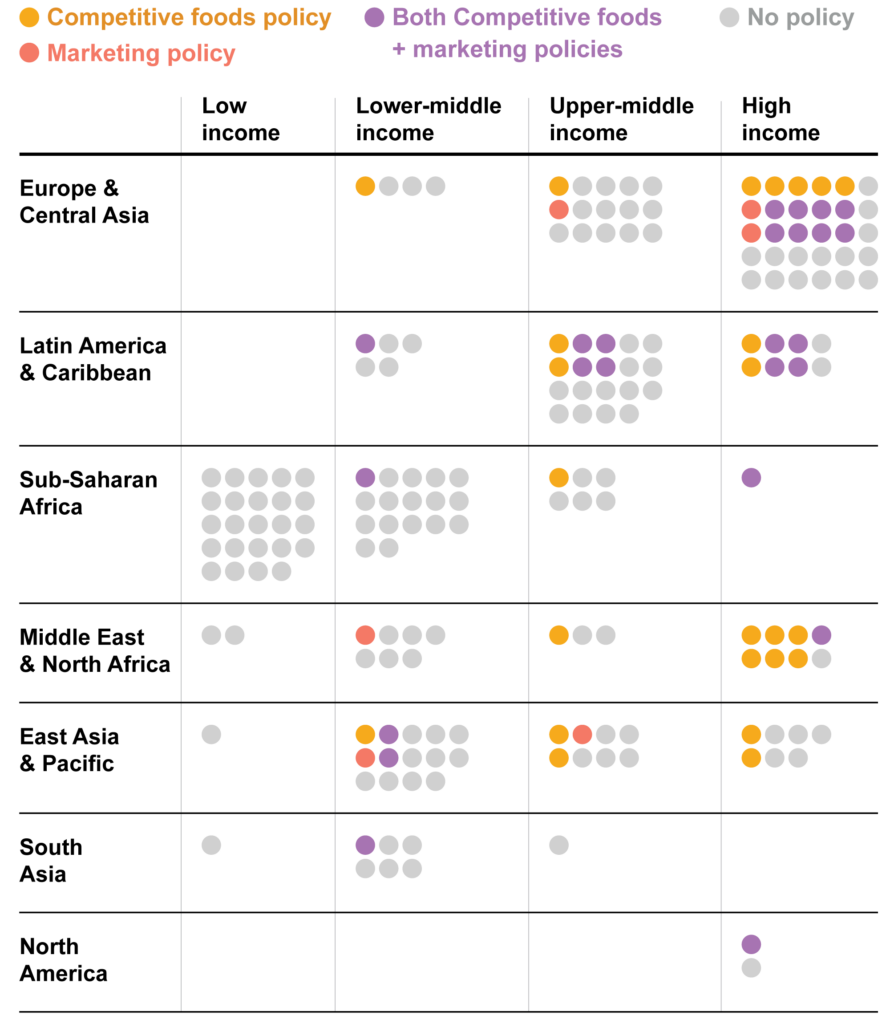

Researchers used a combination of global policy databases, peer-reviewed literature, official government websites, internet searches, and in-country experts to identify policies. For each policy, they gathered information on key features including how foods are nutritionally profiled, whether monitoring and enforcement language are included, and whether policies apply to the area around schools. They also examined trends in policy adoption by country income groups and found that over half of policies were found in high-income countries, and no low-income countries had either policy type.

“We may not have found these policies in low-income countries because of differences in food provision priorities, resources, or availability in schools,” said Barry Popkin, PhD, W.R. Kenan Jr. Distinguished Professor of Nutrition at the UNC Gillings Global School of Public Health, co-director of the Global Food Research Program, and the study’s senior author. “In these countries, the focus may be more on encouraging children to attend school and providing sufficient calories rather than restricting less-healthy foods, but given the double burden of under- and overnutrition in many low-income countries, these policy interventions should be considered to keep childhood obesity levels from worsening.”

Authors also suggest several possible reasons for the lack of greater policy adoption worldwide. For one, adoption could be limited by schools’ reliance on revenue generated by competitive food sales or vending agreements. There may also be a lack of awareness that food marketing is harmful or concern that the food industry could fight attempts at regulation based on rights to free speech/expression. Countries may have other, more pressing policy priorities or may not have the political will or enforcement infrastructure to enact such policies at this time.

“It’s clear that we have a big policy gap worldwide. More countries should consider adopting these policies, particularly in lower-income countries where ultra-processed foods haven’t taken over kids’ diets yet. These products absolutely should not be sold or marketed in schools.“

— DR. BARRY POPKIN

“It’s clear that we have a big policy gap worldwide,” said Popkin. “More countries should consider adopting these policies, particularly in lower-income countries where ultra-processed foods haven’t taken over kids’ diets yet. These products absolutely should not be sold or marketed in schools.”

The authors note a handful of limitations to this study, including the focus only on national-level policies. “We know that many places that have implemented some of these policies at the district, city, state, or province level,” said Emily Busey, MPH, RD, study co-author and research communications manager at the Global Food Research Program at UNC-Chapel Hill. “Given the global scope of this review, we chose to focus on national-level policies to make the search feasible for our team.”

The authors also acknowledge the challenge of finding and interpreting policies written in many different languages and the possibility that policies changed or were enacted after data collection concluded and may not be reflected in this review.

A second, companion scoping review examining national-level policies that restrict provision of categories, nutrients, or ingredients of concern in school meal programs is forthcoming.

This research was funded by Bloomberg Philanthropies.

AUTHORS

Michelle Perry

Kayla Mardin

Grace Chamberlin

Emily Busey

Lindsey Smith Taillie

Francesca Dillman Carpentier

Barry Popkin

Read the full study in Advances in Nutrition

Learn more about school food environment policies.