Two new studies from researchers at the University of Chile and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill have added to the evidence that Chile’s front-of-package nutrient warning labels are an effective way to nudge shoppers towards healthier food choices.

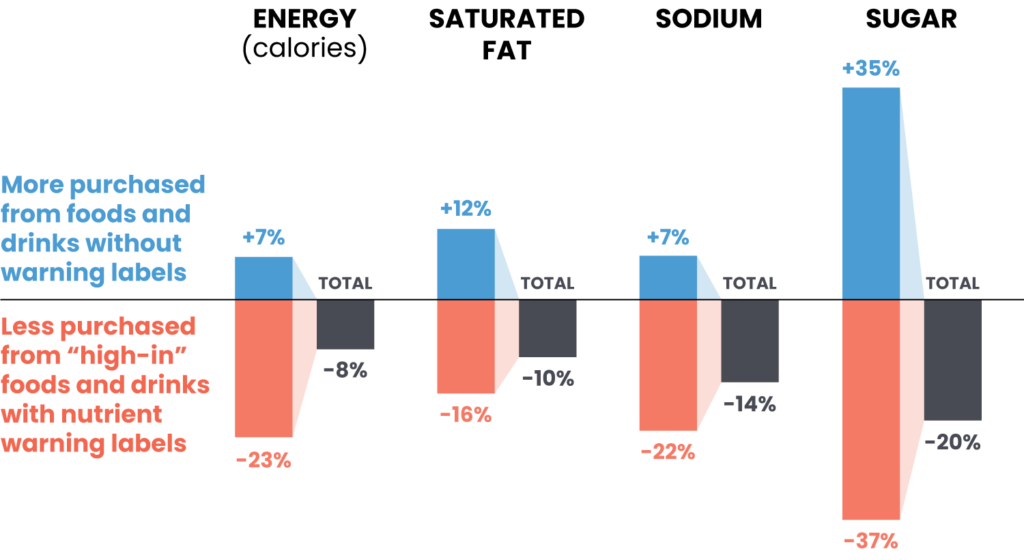

The first, published in PLOS Medicine, evaluated Chileans’ grocery purchases during Phase 2 of Chile’s warning label law and found that households bought 37% less sugar, 22% less sodium, 16% less saturated fat and 23% fewer total calories from products with warning labels.

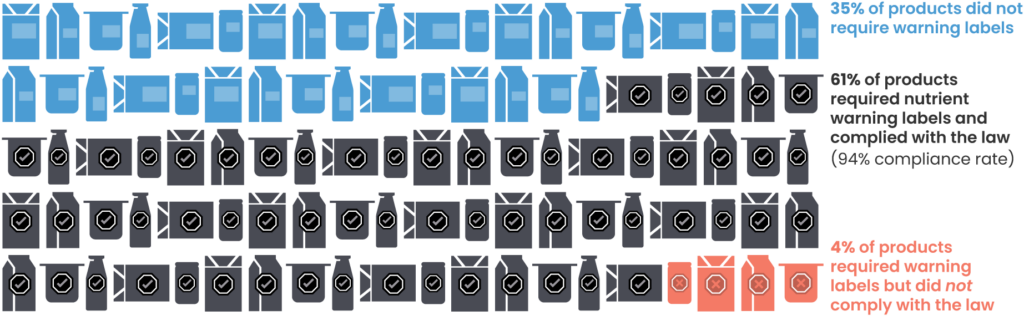

The second study, published in the American Journal of Public Health, found that food and beverage companies in Chile have largely complied with the country’s front-of-package warning label law: In the final and most nutritionally strict phase of the law, researchers found that 94% of products required to carry front-of-package warning labels to indicate high content of sugar, saturated fat, sodium, or calories actually had the appropriate labels on their packages in stores.

Purchase changes

To estimate how Chileans’ shopping choices changed after Phase 2 of the law, researchers at the University of Chile and UNC-Chapel Hill compared data on actual purchases — gathered from 2,844 households in Chile from 2013 to 2019 — to hypothetical food purchases had the law not gone into effect (modeled based on pre-policy trends). Each product in the dataset was profiled by trained nutritionists for nutritional content and ingredients, then categorized as either having or not having a warning label requirement under Chile’s law. They then calculated the differences between the nutritional profile of what purchases were actually made vs. the profile of the expected purchases without a labeling law.

While decreases in purchases of targeted nutrients were partially offset by increases in purchases from products without warning labels, the total change seen across all purchases with and without warning labels was still a significant improvement from pre-policy. Compared to expected purchases had the law not been implemented, Chileans bought 20% less sugar, 14% less sodium, 10% less saturated fat and 8% fewer total calories overall.

Relative difference between nutrients and calories purchased during Phase 2 of Chile’s Law of Food Labeling and Advertising vs. hypothetical expected trends in purchases with no policies:

For calories and sugar, decreases were the greatest among beverage purchases, including 54% fewer calories bought from warning-labeled drinks. Food purchases, on the other hand, had greater decreases in sodium and saturated fat.

“Our findings confirm what we saw in the earliest phase of the law — that people bought less of the concerning nutrients targeted by warning labels — but we can also see now that these changes were even more pronounced in Phase 2,” said Lindsey Smith Taillie, PhD, associate professor of nutrition at UNC-Chapel Hill and the study’s first author. “This tells us that the healthy shifts Chileans made in their shopping habits were maintained or even improved more over time.”

Researchers also found that decreases in purchases of targeted nutrients were very similar across different socioeconomic groups, suggesting that Chile’s policy did not disproportionately advantage or disadvantage any one group.

Food industry compliance

To measure whether food and beverage companies in Chile were complying with warning label law, researchers at the University Of Chile’s Institute of Nutrition and Food Technology reviewed a set of nearly 10,000 products available in supermarkets in Chile during 2020. They identified which products should have a warning label based on their nutritional content (i.e., if they contained added sugars, sodium, or saturated fat and exceeded set nutrient or calorie limits), then observed whether each package requiring warning labels actually displayed them.

Researchers found that 63% of Chile’s packaged food supply had warning labels, with the two most common labels being “high in energy” (found on 39% of products) and “high in sugars” (on 35% of products). A similar portion of products had one warning label (23%), two labels (20%), or three labels (20%), but only 0.5% of products featured all four warning labels.

They also found that compliance was high — 93% for products requiring warning labels for being high in saturated fat, sodium, or energy and 96% for products requiring a high in sugar warning. Two specific food groups stood out for having lower compliance with the labeling law: non-sausage meat products (e.g., hamburgers) with 84% compliance and soups with 85% compliance.

High industry compliance with this mandatory front-of-package labeling law compared to low uptake of voluntary labeling programs such as Health Star Rating labels (found on only 36% of products in Australia and 30% of products in New Zealand) highlights the strength of mandatory labelling policies.

“Our study’s findings show that food industry is able to make changes to their front-of-package labels when this is mandated by the government and there are clear implementation and monitoring guidelines,” said the study’s first author Natalia Rebolledo, PhD, assistant professor of nutrition at the University of Chile’s Institute of Nutrition and Food Technology. “Continuous monitoring is essential for the success of these policies.”

Proliferation of policies

Chile’s trailblazing 2016 food policy package requiring black “stop sign” warning labels on foods and beverages high in nutrients of health concern ignited rapid adoption of eight similar policies throughout the Americas, with more labels currently under development around the world. The country’s innovative law also featured the world’s most comprehensive national restrictions on food marketing to children and banned the sale or promotion of products with warning labels in schools. Other countries have followed suit by incorporating some of these policy elements into their own laws. For example, Mexico followed Chile’s lead when it implemented similar front-of-package nutrient warnings in 2019 and forbid the use of child-appealing characters on packages with warning labels.

These studies are the latest in a series of evaluations that show how the country’s policy package led to improvements in the nutritional quality of Chile’s food supply, changes in social norms and knowledge around foods and drinks with warning labels, and significant drops in children’s exposure to harmful food marketing — all achieved without negative impacts on product prices or employment and wages. Chile’s approach now serves as a model for other countries aiming to improve the food environment to support better population nutrition and health.

Policymakers, health advocates, and researchers in Chile also continue to build on their successes with new interventions to improve public health. In July 2024, the country began requiring warning labels on alcoholic beverages that disclose calorie counts and warn consumers not to drink while driving, if pregnant, or if under 18 years of age. This law will be complemented by advertising restrictions beginning in 2026. In the past year, researchers also piloted a program that will provide low-income Chileans with funds to purchase fresh fruits and vegetables from local neighborhood markets, both supporting the local economy and increasing access to healthier food options.

“We believe that Chile needs to continue leading the efforts for promoting healthier diets,” said Camila Corvalán, MD, PhD, professor of public nutrition at the University of Chile’s Institute of Nutrition and Food Technology and principal investigator of both studies. “This requires advancing the implementation of other food environment policies that discourage the consumption of ultra-processed foods but also support families — especially those with higher vulnerability — in accessing natural foods for example through fruits and vegetable subsidies.”

This research was supported by Bloomberg Philanthropies at part of the Food Policy Program, with additional support from INTA-UNC, INFORMAS, the International Development Research Centre (IDRC), and the National Commission for Scientific and Technological Research (Fondecyt Regular and Fondecyt Postdoctorado).

STUDY 1 AUTHORS

Lindsey Smith Taillie

Maxime Bercholz

Barry Popkin

Natalia Rebolledo

Marcela Reyes

Camila Corvalán

Read more in PLOS Medicine

STUDY 2 AUTHORS

Natalia Rebolledo

Pedro Ferrer-Rosende

Marcela Reyes

Lindsey Smith Taillie

Camila Corvalán

Read more in the American Journal of Public Health

MORE RESEARCH FROM CHILE:

Products changed, but not prices, under Chile’s Law of Food Labeling and Advertising Read more…

Children in Chile saw 73% fewer TV ads for unhealthy foods and drinks following trailblazing marketing restrictions Read more…

After Chile’s labeling and marketing law, drink purchases contained less sugar and more non-nutritive sweeteners, but overall sweetness stayed the same Read more…

Study finds no negative economic impact from Chilean food labeling and advertising law Read more…